The SHSMA has proposed the addition of a new wing to the museum and has received project approval from the City of Sunnyvale. Reconnaissance satellites built in Sunnyvale, and the facilities in the city that monitored them are of profound importance technically, politically, and militarily. This is a significant part of Sunnyvale history, as well as national history, and it is our obligation as curators of history to collect and share it with future generations.

In 1995, the secrecy of the most successful mission for the strategic planning of U.S. foreign policy was lifted. Finally, stories could begin to be told about visionary pioneers who worked in Sunnyvale on a highly classified program called CORONA, and Americans could begin to understand the importance of what those workers had accomplished: Without reconnaissance satellites, no strategic arms agreement would have been possible because neither superpower would allow the other’s observers unlimited access to its military facilities.

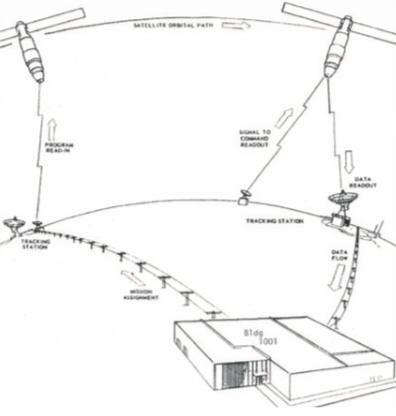

The first Satellite Test Center was a two-story building block structure, called building 1001. When the five-story Blue Cube was built in 1967- 68 (below, left), it was in addition to the original structure. Bldg 1001 is visible on the bottom, right, closest to the 237 freeway.

What kinds of information were the CORONA satellites revealing? Here are some of the highlights:

- Imaged all Soviet medium and long range intercontinental ballistic missiles and complexes

- Imaged each Soviet submarine class from deployment to operational bases

- Provided inventory of Soviet bombers and fighters

- Revealed the presence of Soviet missiles in Egypt protecting the Suez Canal

- Identified Soviet atomic weapon storage installations

- Observed the construction and deployment of the Soviet ocean surface fleet

- Identified the missile launching sites in the People’s Republic of China

A new monitoring facility

When the program began in 1959, the first satellites were monitored from a temporary Satellite Test Center in Palo Alto, just a few rooms with plotting boards adjacent to Lockheed’s computer facility. Having Lockheed engineers at hand was very important to members of the U.S. Air Force, 6594th Test Wing Unit, the organization responsible for operating the Satellite Control Facility. After the initial success of the satellite launches, it became evident that a more permanent control center needed to be built. The Air Force requested and received eleven acres of land in Sunnyvale, next door to Lockheed’s Agena program.

In 1960, a two-story permanent Satellite Test Center came into use on the new property, with the 6594th formally in charge. At the end of 1961, the control center used two computers and could support as many as three satellite missions simultaneously.

Improvements to the Sunnyvale center happened rapidly. In 1965, to handle the number of military space flight projects, a single mission control room was abandoned in favor of separate mission control rooms–one for each flight project. Several large computers added to the center’s capacity to quickly process information.

The Blue Cube

To service flights of the planned Air Force Manned-Orbiting Laboratory, a new windowless ten-story, five-floor blockhouse was built next to the original center. It was completed in 1968 and known informally as the “Blue Cube”. This new test center greatly increased mission-control capabilities. For example, in 1960, the satellite test center made 300 satellite contacts and logged 400 hours of flight operations. In 1982, those numbers had ballooned to 94,000 contacts, and 82,000 hours of flight operation.

On May 25, 1972, Sunnyvale AFS supported the 145th and final launch of the Corona Program, from the original Satellite Control Room in Building 1001. It was terminated as a result of advances in satellite technology. By the time the Corona Program concluded, Corona satellites had provided approximately 800,000 reconnaissance photographs covering approximately 510 million square miles. Following the termination of the Corona Program, the Satellite Control Room Complex continued to be utilized for control of other satellite programs.

The Sunnyvale Air Force Station, where the Blue Cube was located, was renamed several times over the span of its 46-year existence. It was called the Air Force Satellite Test Center,

Photo of the CDC 3600 computer, by Control Data Corporation. 3600 and 3800 computers were introduced in the mid-1960s. By 1967, the Sunnyvale test center contained twelve of these large systems.

the Satellite Control Facility, and, finally, Onizuka AFB in 1994, in honor of Air Force Lt. Colonel Ellison S. Onizuka, an astronaut who died in the Challenger explosion.

The end of the mission

When the Sunnyvale Air Force facility opened in 1960, Sunnyvale was still a rural town, with orchards dominating the landscape. By the late 1970s, the region had become Silicon Valley with a rapidly growing population. To have a national reconnaissance office located in an increasingly populated section of the Bay Area was not ideal.

In 1987, a new Consolidated Space Operations Center was created at Falcon Air Force Base in Colorado Springs. Its role was to serve as back-up to the Sunnyvale location. The Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 forced more space operations away from the Bay Area, and by 1995, primary operations were moved to Colorado Springs.

Telling the Story at Heritage Park Museum

In April 2007, the mission of the National Reconnaissance Office at Onizuka AFS ended after 46 years, and seven years later, the Blue Cube was demolished. Since a lot of information collected over that time period has now been declassified, the SHSMA has taken steps to ensure that the stories of the roles of Lockheed Martin and the personnel who worked in the Blue Cube are not forgotten.

Sources:

Lockheed Martin Newsletter The Star, June 2, 1995

R. Cargill Hall “The Air Force and National Security Space Program 1946-1988”, report declassified on 30 June 2014. Governmentattic.org

By Margarete Minar